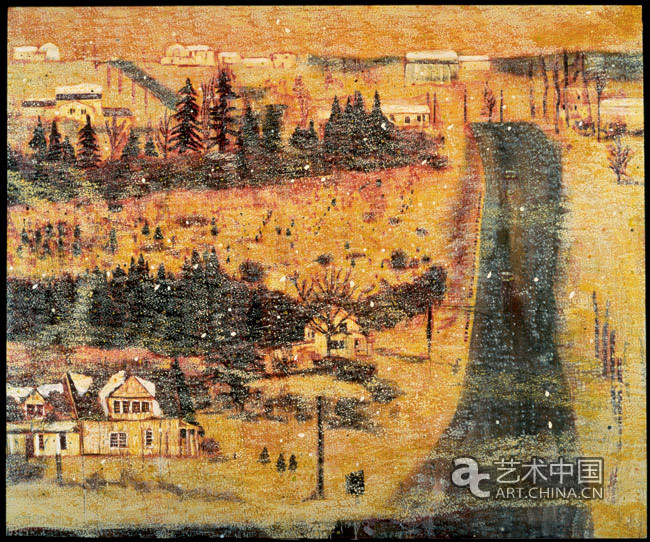

彼得多伊格-《山屋》 |

| 艺术中国 | 时间: 2010-01-29 18:40:08 | 文章来源: 艺术中国 |

|

彼得多伊格-《山屋》 Peter Doig Hill Houses 1990-1991 Oil on canvas 200.1 x 240.3 cm 彼得.多伊格 山屋, 1990-1991 布面油画 200.1 x 240.3 cm

1990年,彼得•多伊格刚刚从切尔西艺术学院(Chelsea School of Art)修完硕士课程,并作为一名白教堂艺术家奖(Whitechapel Artists Award)得主开始声名鹊起。他的画作摒弃主流而另辟蹊径:“20世纪80年代晚期和20世纪90年代早期大多数作品看起来都给人纯净、当代、灵巧之感……我有意创作出看起来质朴而有手工感的作品。” 《山屋》展示了多伊格与众不同之处,这一海市蜃楼般的冷峻意象传递出既有叙述又有回忆的意蕴,引领思绪超越无框的画布,给人以莫奈的“水仙”般的历史感。 这幅画作分散的焦点和跳跃的视角导致了理查德•希夫(Richard Shiff)所谓的“漫游的激动”。景象通过朦胧质感令人惊讶,就像迎着一辆朝着天际飞驰的车辆扑面而来映入风挡的景象。巨大竖条状的道路本来应该将我们引入画面,却反而冲到了原本平坦的显像面的最前面。模糊的电线杆无法在踩着狐步飘然而过时量出画面。只是在画面上部的三分之一处才出现了小孔窗、道路的甩尾处—距离感的提示。这里是崇高与庸俗的汇聚处,在这里情感的标识物——杏仁糖般的房屋和童话般的松树——与荒野的恐怖形成了鲜明的对比。 多伊格的经历是一种回归。他于1959年生于爱丁堡,他的家庭在定居加拿大之前在特立尼达生活了几年;多伊格随后搬回英国,到圣马丁艺术学校(St Martin’s School of Art)学习,其后又回到加拿大(他曾在蒙特利尔做过电影布景画师);后来他又回到伦敦攻读硕士学位,而现在生活在特立尼达岛。朱迪思•奈斯比特(Judith Nesbitt)评价说:“令人惊奇的是,他对主题的追求是与他阶段性地地理位置变化联系在一起的,而只有当他离开一定距离之后,其直接地理环境的视觉刺激才会释放出来。”然而正如所说的大型画布激发了他青年时期的巨幅加拿大风光作品一样,多伊格摒弃了显而易见的题材。在回忆自己的早期作品时,他坚称:“它们不是关于加拿大的画作(尽管有些确实是),而是蕴含某种也许有些大众化概念的作品——将某种‘简朴’引入艺术之中。”这一简朴概念有助于在《山屋》这幅作品,这样一个古老的茶盘一样泛着黄色的作品与那种“纯净、当代、和灵巧之感”之间制造出数以百英里计的距离。有关开阔道路的幻想、出于惊恐的战栗与渴望:我们不知不觉进入这样的意象之中,这正是垃圾摇滚的纪念品(多伊格收藏的磁带中就有涅磐乐队1991年发行的受到狂热崇拜的专辑“没关系”(Nevermind))。 有人认为这幅作品源于刊登在《国家地理》杂志上的一幅照片,那幅照片据认为多少唤起了作者对童年时代魁北克某地的回忆。但即使如此,《山屋》和所有其他作品一样依然是关于绘画的作品。值得注意的是,多伊格在其光学效果以及圣诞卡涵义方面放大了雪花的表面性:“雪花还是同样的大小,她是不可透视的,我所喜欢的是有关雪的‘观念’的这一概念。她变得像一层纱幕,使你透过纱幕看出去。”对于事物的“观念”的偏好以及对透过柔和而无序的颜料层次凝视的强调使画面容易受到推论的影响,这一点与多伊格的工作方式相一致。他喜欢将未完成的画作搁置一段时间进行构思。他曾经描述过这么做的必要性:一开始就在画室的桌上和地上到处放好打开了的颜料罐,随后把一幅画单独放置很长时间,反复斟酌,等以后再回来接着画。 Peter Doig In 1990, Peter Doig had just finished an MA at Chelsea School of Art and as a winner of the Whitechapel Artists Award was on the cusp of recognition. He was producing paintings that beat a path away from the mainstream: ‘In the late 1980s and early 1990s most art had a clean, contemporary, slick look … I purposely made works that were handmade and homely looking.’ Distinctive Doig territory is staked out in Hill Houses, a frosty mirage that whiffs of narrative and memory, beckoning beyond the unframed canvas to something as un-contemporary as Monet’s ‘Water Lilies’. This is a picture whose scattered focus and jumps in perspective result in what Richard Shiff identifies as a ‘sensation of roaming’. Through the mistiness, the view takes us by surprise, as if swooping into the windscreen of a car as it races over the skyline. The road, a big vertical stripe, ought to guide us into the scene, but instead forefronts the flatness of the picture plane. Telegraph poles are blurry, not so much pacing out the landscape as shimmying across it. Only in the top third is distance suggested – pinprick windows, a tail-flick of road. It is a meeting ground for the sublime and the kitsch, where sentimental markers, those marzipan houses and fairytale pines, effectively strike a match against the terror of the wilderness. Doig’s story is one of returns. Born in Edinburgh in 1959, his family spent a couple of years in Trinidad before settling in Canada; Doig moved back to Britain, to study at St Martin’s School of Art, thereafter returning to Canada (he had a stint as scene painter for film sets in Montreal); it was back to London for his MA, and he now lives in Trinidad. Judith Nesbitt remarks, ‘His search for his subject has been curiously linked to his periodic geographical displacement, whereby the visual stimulus of his immediate geographic environment becomes released only with distance.’ Yet as much as the large-scale canvases are said to evoke the vast Canadian landscape of his youth, Doig screens off obvious subject matter. Reflecting on early works, he insists, ‘They weren’t paintings of Canada (though some were) but paintings of an idea of something that was maybe folk – bringing a sort of “homeliness” into art.’ This idea of homeliness serves to put hundreds of miles between Hill Houses, yellow-stained like an ancient tea tray, and that ‘clean, contemporary, slick look’. Fantasies of the open road, shivers of fear and longing: this is an image that creeps up on us, a souvenir of grunge (Nirvana’s cult album Nevermind, 1991, is counted among Doig’s collection of cassettes). A photograph from National Geographic, loosely evoking a childhood spot in Quebec, has been isolated as a source, but even so, Hill Houses is a painting about painting as much as anything else. Notably, Doig amplifies the superficiality of snow in terms of its optical effect as well as its Christmas card connotations: ‘The snow is all the same size, it’s not perspectival, it’s this notion of the “idea” of snow which I like. It becomes like a screen, making you look through it.’ This predilection for the ‘idea’ of things, and the emphasis on looking through the soft, untidy layers of paint, render the picture open to inference, correspondent to Doig’s working method. He prefers to keep paintings unfinished for a period of gestation. He has described the need, on starting out, to open pots of paint all over the studio table and floor, and later to leave a painting alone for long stretches, being thought about, waiting to be returned to. D.F. |

| 注:凡注明 “艺术中国” 字样的视频、图片或文字内容均属于本网站专稿,如需转载图片请保留 “艺术中国” 水印,转载文字内容请注明来源艺术中国,否则本网站将依据《信息网络传播权保护条例》维护网络知识产权。 |